Small Rituals (Brian L.)

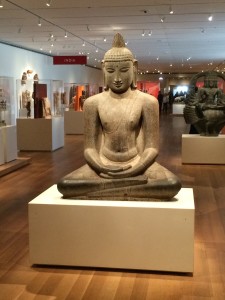

For a Buddhist, it can be disconcerting to walk through the Asian art wing of the Art Institute of Chicago. Eighth-century Bodhisattva statues flank the entrance to exhibition spaces filled with artifacts. Museum visitors stream by on the search for a famous Van Gogh or Matisse, barely turning their heads in acknowledgement of these ancient images. Ritual instruments, deity figures and carefully preserved paintings line the walls and fill the floor space.

These artifacts are, of course, practical in origin. Religiously practical—as opposed to practically religious—these objects were designed and made for personal, communal, and heavenly ritual purposes. Now, they fulfill a different function, serving as examples of cultures and religion far removed from the tall towers and placid lakefront of downtown Chicago.

The Art Institute of Chicago is one of the world’s premier museums, an encyclopedic collection of approximately three hundred thousand objects housed in almost one million square feet of museum space. To be fair, the multiple problems associated with incorporating ritual items into a museum—a particular kind of space devoted to a particular understanding of objects—is by no means unique to the Art Institute, nor are the many Asian art professionals both in the Art Institute and beyond unconcerned with these issues. But the fact remains that the museum’s standard of use and care for these objects is quite distinct from that of the temple or monastery for which many of these objects were first made. Use, in the museum, is defined in terms of contemplation, study, and preservation.

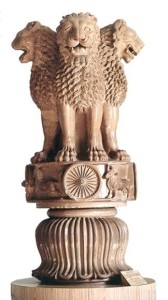

It is safe to say that the majority of people walking through the halls of the Art Institute of Chicago are neither Buddhist nor Hindu. In contrast, the Sarnath Museum, a museum run by the Archaeological Survey of India near Varanasi in the northern part of the country, displays some of the incredible grey schist and sandstone sculptures found at the site. Sarnath is said to be where the Buddha first taught the Four Noble Truths, where the wheel of Dharma began to turn and the Sangha, or community of practitioners, was established. The modern day Sarnath Museum, like the Art Institute of Chicago, aspires to similar museological conventions: careful preservation of the objects for future generations, disciplined study, and visual display.

However, many who walk those halls have a different relationship with these objects. Museum visitors touch the statues constantly, or, to use a better term in this context, the deity-images. Guards appear mildly exasperated, but also unsurprised. It is unclear whether the worn sections at the statue’s base are from the object’s time in temple settings, or from its time displayed at the Sarnath Museum. The Sarnath Museum, far more so than the Art Institute, highlights the differing value systems at work when religious objects are preserved and displayed in museum settings.

What does it mean to remove an object, like a statue of the Buddha, from its context of ritual use? This question has come continually to my mind as I, over the past two years as a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, traversed that hallway hundreds of times. My own particular background, as a Buddhist with training in art history, makes this particular point of intersection intensely apparent.

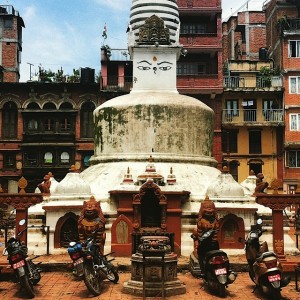

My solutions are small, and personal. I try (at least, when I think I won’t look too bizarre to my companions) to walk to the left of the major, central images, as one would when circumambulating around a ‘real’ Buddhist temple. I have even, on occasion, walked clockwise around the multi-block Art Institute campus, when I had the time. Or, more honestly, whenever I needed to be reminded that these objects and the museum in which they are housed are but one piece of the puzzle, one set of available values. Even though these gestures are tiny—practically unnoticeable—they bring me back, for a moment, to remember the meaning and values these images were originally intended to inspire.

How do we relate to our religion, our practice, our ethical grounding? Should we treat these fundamental aspects of our life like statues in the museum, as objects to be collected, studied, considered, written about and displayed to others? Or are our ethics something to be put into practice, something we have to live with, to touch, to know intimately? It is easy to adopt an intellectually removed attitude towards our practice, analyzing and debating. And it can be just as easy to forget the necessity of living with and through these values, rather than collecting and preserving them for some idealized future. Our ethics, or our religious practice, need to be handled, to be treated both carefully and intimately, in order to function in our lives. If we are too careful with them, placing them on high pedestals behind thick glass, we risk passing them by.

[BRIAN tells us: I am an artist, writer, curator and gallery manager. That is in order of priority. Buddhist is also certainly on that list, though its position is always less clear. Here, I will be thinking about the deep intersections of art and Buddhism, focusing on the personal and observational rather than the historical or technical. Of course, priorities can always shift.]

Read More